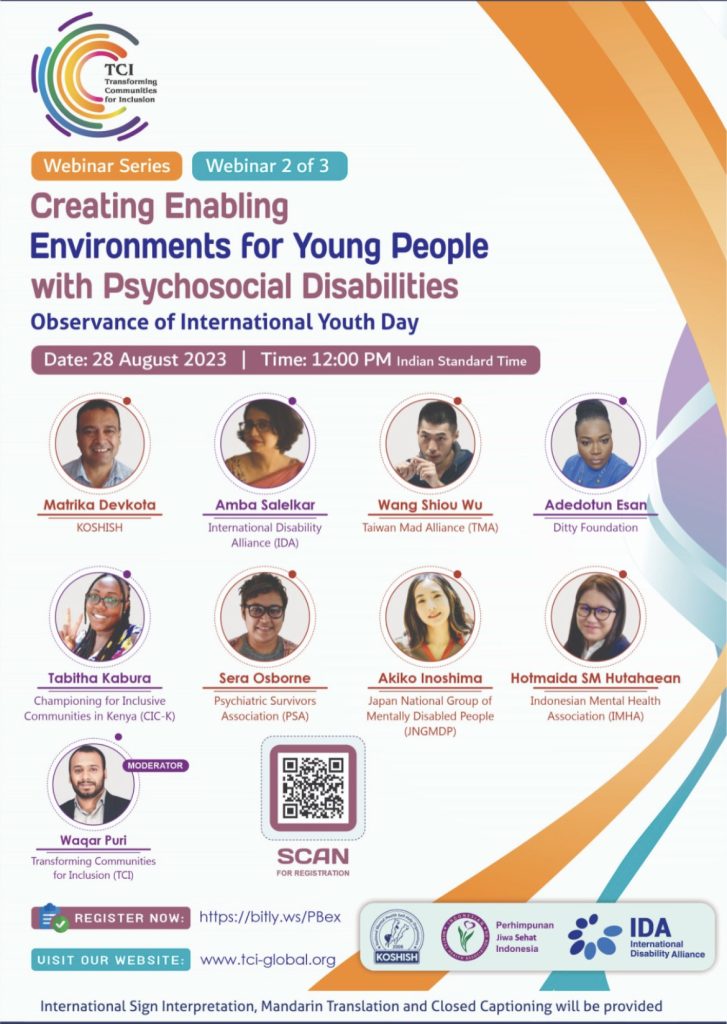

【活動報告】8.28精神障害のある若者たちのための環境づくりとは (登壇&アーカイブ配信)

国連障害者権利条約19条の実施を目的にした国際的な精神障害のある人にらによって組織されるTransforming Communities for Inclusion (TCI)が主催するオンラインウェビナーセミナーが8月28日に開催されました。テーマは「精神障害のある若者たちのための環境づくりとは」。ポルケの事務局スタッフの猪島章子が日本のユースを代表して登壇をしました。当日の模様がアーカイブ配信で視聴いただけます。どうぞご覧ください。

▼猪島さん発表原稿

Thank you to the fantastic co-panelists and organizers for inviting me to this webinar. Hello, I am Akiko Inoshima, an administrative staff of [Porque, the Organization of Persons with Psychosocial Disabilities], a member of the Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People (JNGMDP). I am 24 years old and have lived with psychosocial disabilities since I was 16. Today, I am honored to be given opportunities to present the problems that young people with psychosocial disabilities in Japan face today and the further development needed to expand inclusion in society.

Psychosocial health in young people has been one of the Japan’s most grave social problems. Among the age group of 15 to 35, the top cause of death is suicide. Moreover, the data shows that approximately 40% of females in their 20s and 30s had attempted suicide. Regarding teenagers, the “Futoko-ji” has become an ever-impending national problem. Futoko-ji refers to the students who refuse to go to school for over a month, mainly due to psychosocial issues arising from bullying, poor educational performance, or family background. Its number has been increasing gradually over the last decade, and by last year, the government announced that 1 in 20 students in middle schools was Futoko-ji. Thus, we have reached the point where integral and robust measures for helping youth with psychosocial problems have become indispensable for social survival and safety.

However, peer support activities among youth with psychosocial problems are yet scarce. In Japan, young generations rarely participate in NGOs or organizations relevant to this topic. In addition, few recovery colleges or organizations target those age groups. Within exceptional organizations which do include young people, mainly adults, are organizers or supervisors, leaving young people only passive roles in activities.

I believe this inactive attitude toward peer activities resulted partly from social stigma. The social stigma against psychosocial problems is severe among youth, especially with the expansion of SNS. On the internet, people like us are often ridiculed with derogatory slang. For example, we are commonly called “land mines” because there is a strong narrative that claims if you encounter people with psychosocial problems without prior warning, you will be involved in troublesome issues later on. On the contrary, psychosocial health literacy education, which is proven to alleviate the stigma in many countries, is hardly incorporated into Japanese education. It was only last year that psychosocial health education became an obligatory subject in high school.

The severe examination ordeal is another primary reason for the weakness of the peer activities. In 2020, more than 95% of the population went to high school, of which over half went to college or university. [1] This means if you are one step off from the “ideal educational path,” you would feel like a complete failure in our society. Therefore, for young Japanese people, the first question that comes to mind when encountering the first psychosis is, “How can I continue my education and prepare for entrance exams and not disappoint my family?” not “How can I deal with this new aspect of mine or connect with a peer?” This enormous social pressure to enroll in “good “ schools hinders us from taking enough time to heal or reach out to peers.

To encourage peer support among the Japanese youth, enhancing community-based support is essential. In 2018, the average period of psychiatric hospital stays in Japan was a staggering length of 274 days. No need to mention that this was the longest among the OECD countries but also was ten times longer than its average. If the young Japanese had been in hospital for that lengthy period, they would highly likely have been forced to quit school, give up on careers, and lose connection with the community, which is precisely what happened to me at 16. Therefore, to protect our future and self-esteem, the shift to community-based care and the shortening of hospital stays should be strongly encouraged. This point was also highly urged by the Committee of CRPD in 2022 toward the government.

Along with this policy-wise transition, the citizen sectors should also promote peer activity among youth both nationally and globally. First, the discriminatory statement toward psychosocial disabilities should be replaced with the human rights concerning one. This would make us feel safe to disclose our disabilities and ask for reasonable accommodations at schools or workplaces. Secondly, interaction with peers would prevent us from falling into self-hatred for not being on the “standard, desired educational path” we are so socially pressured to follow. Such continuous work will someday make Japanese society realize that there is no ideal single career path that all young people should take and accept the individual’s uniqueness and ways to contribute to the community.

To conclude, we strongly assert that young people with psychosocial disabilities are still not fully included in the Japanese community, primarily due to online social stigma, intense Institutionalization, weak peer support, and tight student educational requirements. We desperately ask for global help and cooperation like today’s webinar to lift those barriers to form a society that includes and respects all members.

※日本語訳

このウェビナーにお招きいただいた素晴らしい共同パネリストの方々、主催者の方々に感謝いたします。どうも、全国「精神病者」集団のメンバーである「精神障害当事者会ポルケ」の事務局スタッフ、猪島章子です。私は今24歳ですが、16歳から心理社会的障害とともに生きてきました。今日は、日本の心理社会的障害を持つ若者が直面している問題や、社会へのインクルージョンを拡大するために必要なさらなる発展について発表する機会をいただき、光栄に思っております。

若者の心理社会的健康は、日本の最も深刻な社会問題のひとつです。15歳から35歳の年齢層では、死因のトップが自殺です。さらに、20代、30代の女性の約4割が自殺未遂を経験しているというデータもあります。10代に関しては、「不登校」が国民的な問題となっています。 不登校とは、いじめや学業不振、家庭環境などによる心理社会的な問題を主な原因として、1ヶ月以上学校に行かない生徒のことです。その数はここ10年で徐々に増加し、昨年には中学校の生徒の20人に1人が不登校であると政府が発表しました。このように、心理社会的問題を抱える青少年を支援するための一体的で強固な対策が、社会の存続と安全のために不可欠となるところまで来ています。

しかし、心理社会的問題を抱える青少年のピアサポート活動はまだ少ないのが現状です。日本では、若い世代がこのテーマに関連するNGOや団体に参加することはほとんどありません。加えて、これらの年齢層を対象としたリカバリーカレッジや組織も少ないです。例外的に若い世代が参加している団体でも、主に大人が主催者や監督者となっており、若い世代は受動的な役割しか担っていません。

このようなピア活動に対する消極的な態度の原因の一つとして、社会的スティグマが挙げられると思います。特にSNSの普及により、若者の心理社会的問題に対する社会的スティグマは深刻です。インターネット上では、私たちのような人間はしばしば侮蔑的なスラングで揶揄されます。例えば、俗に「地雷」と呼ばれていますが、これは、心理社会的な問題を抱えた人に何の前触れもなく遭遇すると、後々厄介な問題に巻き込まれるという偏見が強いからです。それどころか、多くの国でスティグマを緩和することが証明されているメンタルヘルスリテラシー教育は、日本の教育ではほとんど取り入れられていません。高校でメンタルヘルスリテラシー教育が必修科目になったのは、つい昨年のことです。

厳しい受験戦争も、ピア活動の弱さの主な原因です。 2020年では、日本の人口の95%以上が高校に進学し、そのうち半数以上が大学や短大に進学しています。 つまり、「理想的な教育の道」から一歩でも外れると、社会的落伍者のように感じてしまうのです。したがって、日本の若者にとって、最初の精神病に遭遇したときに最初に思い浮かぶ疑問は、”自分のこの新しい側面に対処するために、ピアと繋がりたい “ではなく、”どうすれば家族を失望させずに進学し、受験に備えることができるのか “です。この「良い」学校に入学しなければならないという大きな社会的プレッシャーが、私たちが十分な治療期間や、ピア活動に十分な時間を取ることを妨げています。

日本の若者のピアサポートを促進するためには、地域に根ざした支援を強化することが必要です。2018年には、日本における精神科病院の平均在院日数は274日という驚異的な長さでした。これはOECD加盟国の中で最長であることは言うまでもありませんが、平均の10倍も長かったのです。もし日本の若者がこれほど長い期間入院していたら、学校を退学し、キャリアを諦め、地域社会とのつながりを失うことを余儀なくされる可能性が非常に高いです。したがって、私たちの将来と自尊心を守るために、地域密着型ケアへの移行と入院期間の短縮は強く奨励されるべきです。この点は、2022年にCRPD委員会も日本政府に対して強く訴えていました。

このような政策的な転換とともに、市民セクターは青少年のピア活動を国内外に広めるべきです。まず、心理社会的障害に対する差別的な記述を、人権を配慮したものに改めるべきです。そうすれば、私たちは安心して自分の障害を公表し、学校や職場で合理的配慮を求めることができます。第二に、ピアとの交流は、私たちが社会的に強いられている「標準的で望ましい教育の道」を歩んでいないことに対する、自己嫌悪に陥ることを防ぐこともできます。このような活動は、いつの日か日本社会に、すべての若者が進むべき理想的なただ一つの道などはなく、一人一人の個性と地域社会への貢献の方法に寛容である必要性を認識させることでしょう。

まとめますと、日本の心理社会的障害を持つ若者は、主にオンライン社会的スティグマ、強烈な施設収容、弱いピアサポート、厳しい学生教育要件のために、コミュニティにまだ十分に参画できていないことを強く懸念しています。私たちは、今日のウェビナーのような世界的な支援と協力を切に求めており、これらの障壁を取り除いて、みんなが尊重される、インクルーシブな社会になることを切に祈っております。

※www.DeepL.com/Translator(無料版)で翻訳しました。